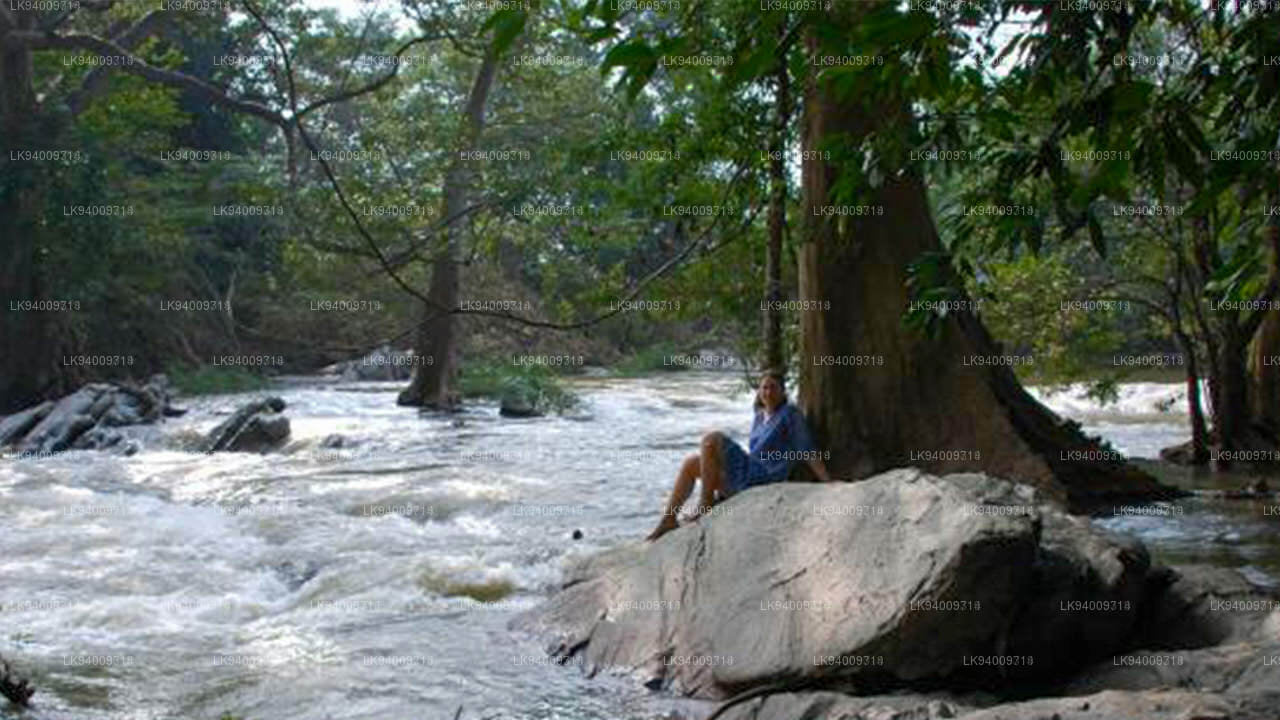

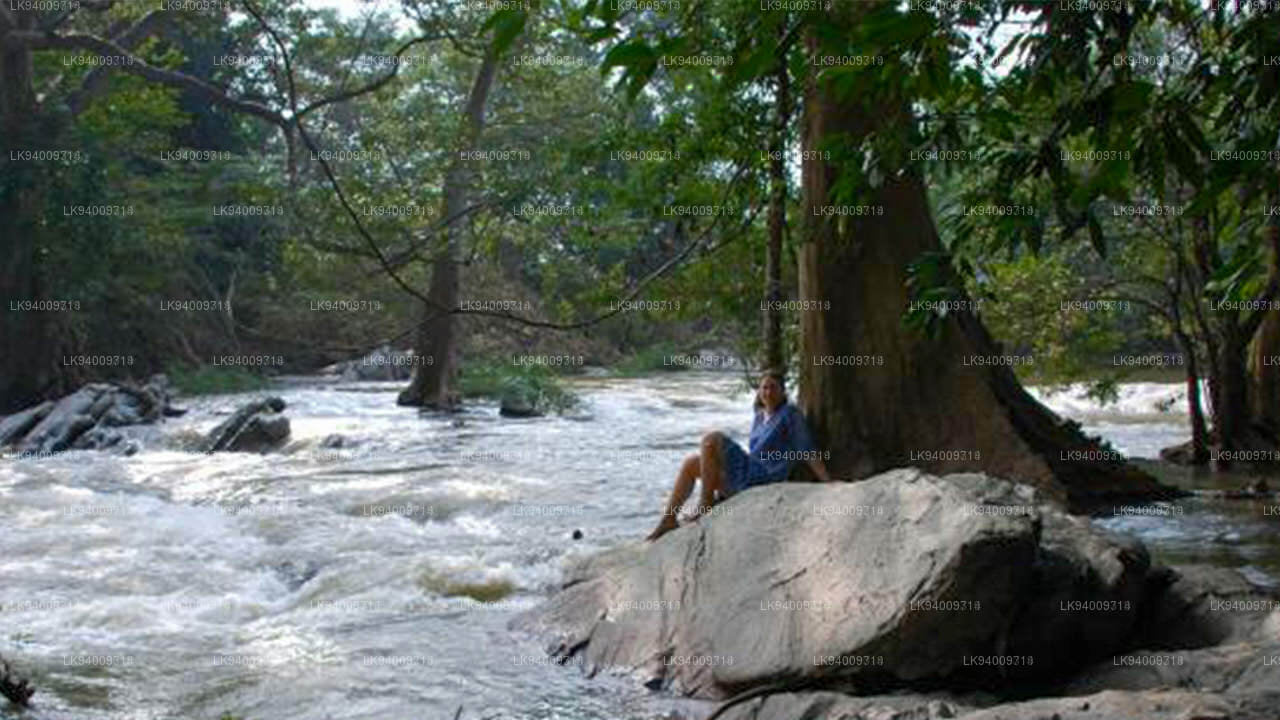

Rivers

The rich network of rivers in Sri Lanka make the island an oasis at any time of year, naturally watering the paradise garden with its splendid heritage. The highest concentration of rivers and lakes is found in the south-west of the country, making it possibly the most fertile area in Sri Lanka.

Kala Oya (කලා ඔය)

Sri Lanka has one of the oldest traditions of irrigation in the world, dating back as far back as 500 BC. The famous dictum of the epic hero King Parakrama Bahu I (1153-86) states “let not even one drop of water that falls on the earth in the form of rain be allowed to reach the sea without being first made useful to man”. It was around these ancient tank (water storage reservoir) irrigation systems that the economy and human settlements of early Sri Lankan society were organised into a “hydraulic civilization”. Unlike in the case of most ancient civilizations, which grew in fertile river valleys and floodwater retention areas, Sri Lankan hydraulic societies were based on reservoir systems and control devices or biso-kotuwas for the release of irrigation water. It has been reported that at the peak of its development, the ancient Sri Lankan hydraulic engineers were even called upon to serve in other countries. Today’s map of Sri Lanka, especially the Dry Zone, is dotted with literally thousands of ancient tanks of varying sizes and shapes, some operational and others long abandoned. These ancient tank systems have both ecological and biological importance. A key issue is seasonality and duration of water retention, which has a significant influence on their biodiversity and ecology. Due to natural processes water levels are very low during the dry season, and many tanks dry out completely before being filled again in the rainy season. Their use for grazing cattle during the dry season maintains high levels of nutrients in the tanks – which in turn supports high levels of aquatic biodiversity.

-

Malwathu Oya (මල්වතු ඔය)

Malwathu Oya (මල්වතු ඔය)The Malvathu River long river in Sri Lanka, connecting the city of Anuradhapura, which was the capital of the country for over 15 centuries, to the coast of Mannar. It currently ranks as the second longest river in the country, with a great historic significance.

-

Kelani River (කැලණි ගඟ)

Kelani River (කැලණි ගඟ)The Kelani River is a 145-kilometre-long (90 mi) river in Sri Lanka. Ranking as the fourth-longest river in the country, it stretches from the Sri Pada Mountain Range to Colombo. It flows through or borders the Sri Lankan districts of Nuwara Eliya, Ratnapura, Kegalle, Gampaha and Colombo.

-

Yan Oya (යාන් ඔය)

Yan Oya (යාන් ඔය)The Yan Oya is the fifth-longest river of Sri Lanka. It measures approximately 142 km (88 mi) in length. Its catchment area receives approximately 2,371 million cubic metres of rain per year, and approximately 17 percent of the water reaches the sea. It has a catchment area of 1,520 square kilometres.

-

Walawe River (වලවේ ගඟ)

Walawe River (වලවේ ගඟ)The southern region of Sri Lanka is exalted by a bushel of enthralling and glorified rivers and the Walawe River is one of them. Gently flowing through the Udawalawe National Park, the Walawe River provides water for a multitude of species of mesmerising fauna.

-

Kalu Ganga (කළු ගඟ)

Kalu Ganga (කළු ගඟ)Kalu Ganga is a river in Sri Lanka. Measuring 129 km (80 mi) in length, the river originates from Sri Padhaya and reach the sea at Kalutara. The Black River flows through the Ratnapura and the Kalutara District and pass the city Ratnapura. The mountainous forests in the Central Province and the Sinharaja Forest Reserve are the main sources of water for the river.

-

Maha Oya (මහ ඔය)

Maha Oya (මහ ඔය)The Maha Oya is a major stream in the Sabaragamuwa Province of Sri Lanka. It measures approximately 134 km (83 mi) in length. It runs across four provinces and five districts. Maha Oya has 14 Water supply networks to serve the need of water and more than 1 million people live by the river.

-

Gin Ganga (ගිං ගඟ)

Gin Ganga (ගිං ගඟ)The Gin Ganga, is a 115.9 km (72 mi) long river situated in Galle District of Sri Lanka. The river's headwaters are located in the Gongala Mountain range, near Deniyaya, bordering the Sinharaja Forest Reserve.

-

Kala Oya (කලා ඔය)

Kala Oya (කලා ඔය)It was around these ancient tank (water storage reservoir) irrigation systems that the economy and human settlements of early Sri Lankan society were organised into a “hydraulic civilization”.

-

Deduru Oya (දැදුරු ඔය)

Deduru Oya (දැදුරු ඔය)The Deduru Oya Dam is an embankment dam built across the Deduru River in Kurunegala District of Sri Lanka. Built in 2014, the primary purpose of the dam is to retain approximately a billion cubic metres of water for irrigation purposes, which would otherwise flow out to sea.

-

Maduru Oya (මාදුරු ඔය)

Maduru Oya (මාදුරු ඔය)The Maduru Oya is a major stream in the North Central Province of Sri Lanka. It is approximately 135 km (84 mi) in length. Its catchment area receives approximately 3,060 million cubic metres of rain per year, and approximately 26 percent of the water reaches the sea.

-

Kumbukkan Oya (කුඹුක්කන් ඔය)

Kumbukkan Oya (කුඹුක්කන් ඔය)The Kumbukkan Oya is the twelfth-longest river of Sri Lanka. It is approximately 116 km (72 mi) long. It runs across two provinces and two districts. Its catchment area receives approximately 2,115 million cubic metres of rain per year, and approximately 12 percent of the water reaches the sea.

-

Mi Oya (මී ඔය)

Mi Oya (මී ඔය)The Mi oya is a 108 km (67 mi) long river, in North Western of Sri Lanka. It is the fifteenth-longest river in Sri Lanka. It begins in Saliyagama and flows northwest, emptying into the Indian Ocean thru Puttalam.